There are several criteria that according to broad consensus a currency must fulfill in order to be considered a ‘good’ medium of transaction. These are qualities such as non-perishability, ease of transport/exchange, stability of value and general acceptance. In this short write-up, I will briefly detail why, in fact, a currency that is too stable and retains its value too well – characteristics that would be considered economically desirable by the orthodoxy – makes for poor, depending on degree even entirely unsuitable, money.

The key principle to be grasped here, is that there really only are two things one can do with currency: One can either spend it or save it (in order to spend it at a later date). Naturally, as one precludes the other, this decision involves an economic trade-off wherein presently realizable utility (buy pistachio ice-cream now) is weighed against future expected realizable utility (buy pistachio ice-cream later).

There are many factors that (rationally should) influence this weighing process, such as planning horizon of the agent, level of blood sugar (I find it very difficult to plan for the future when I am hungry) and, of course, the expected rate of return (of utility) on postponing consumption.

To complicate the matter, not all spending relates to the direct satisfaction of human needs but instead leads to increased projected realizable utility through a return on the decision to spend. This is also known as investment. (Note, that though I here differentiate between investment as a form of spending/consumption and saving (a choice to consume later), from the modern macro-economic point of vantage, saving must be investment. One of the core functions of the financial system is to spend (invest) savings.) It is the intimate entanglement of saving (deferred consumption) with investment (spending with an expectation of positive return) via currency that enables the continuous functioning of the economic system.

To understand this, one needs to think through a couple of different scenarios.

Suppose that you are in possession of money and that there is a good or service that you could acquire if you were to spend it which would (partially) meet some basic biological need (say hunger, for instance) and thus provide utility. Further, there is an alternate good or service, which, if bought, would generate a return over a period of time – an investment.

Your options regarding the use of your money are the following:

A) You choose to spend the money on the consumer good, realizing some utility now but foregoing the ability to spend in the future.

B) You buy the second good or service – the investment – realize its return over the investment horizon and later face the same three choices as now.

C) You do not buy anything, that is, you choose to save.

We can see that our decision-making, if rationally maximizing our realized utility, will depend on a series of factors and how they relate to one another quantitively. For instance, if the return of B is zero in real terms – the equivalent of there not being an investment – choices B and C are functionally equivalent. If B, however, provides a positive real return, then C is a strictly sub-optimal choice and should never be made.

Whether you will choose A or B will depend on the urgency of your desire to realize utility (sooner rather than later) and how much expected real return the investment provides.

Interestingly, these options available to you can also be viewed as a decision about how much of your purchasing power you want to hold in which type of medium – monetary or non-monetary. It presents a trade-off between the two types and in some sense is strangely existential, seeing as it is the aggregate decision-making of economic participants that determines which assets are regarded as monetary or non-monetary. An odd thought, is it not – just imagine a sudden reevaluation from one to the other. Of course, this need not be purely theoretical – whenever a new currency becomes accepted or an old one loses its support, a thing transitions from the state of being valued solely as a (physical) good to a monetary state and back, respectively. Seeing as humans have monetarized a great number of disparate commodities/assets/privileges over the past millennia, it is more than just idle rumination to think about the mechanisms that make or break money.

To examine said mechanisms we need to expand the dynamics of our three-choice-model. While price-fluctuation of investments and consumer goods is obvious, this variability also implies price-variability of money itself. If all/most purchasables systematically shift up or down in nominal price, this is indistinguishable from inflation or deflation of the monetary asset in which the exchange is denominated. How might this affect your spending choices?

Clearly, if you anticipate that the good you desire will decline in price for the foreseeable future, this decreases your desire to spend in the immediate present and makes it more desirable to save or even invest. This can feed on itself and cause a deflationary spiral where consumer demand slows, driving down prices, incentivizing further delay of purchases, triggering further price collapse causing yet more delay and so forth. After all, why buy a new couch today if in another two weeks you expect it to cost half? What may appear like a great deal for the individual can, over time and in aggregate, turn out to actually be catastrophic since if the employees at the couch manufacturer get laid off because of flagging revenues, they lose out on income and draw on savings & investments which they cannot spend as readily, causing further weakening of demand, prices, profits, employment, investment and overall economic activity. Not great. This is one way money may fail – sustained deflation and deferred spending slowing circulation to a crawl, clotting crucial commercial arteries and giving the economy a heart-attack.

Naturally, the opposite of sustained deflation, run-away inflation and eventually hyperinflation may also occur. If prices keep rising, you may become tempted to begin stockpiling, shifting forward demand and putting further inflationary pressure on prices. As the buying power per unit of currency nosedives, your need to consume more and more quickly skyrockets. Investment becomes discouraged (as does saving, since real returns on deposits are directly tied to the currency and the profitability of investments), especially where there is great up-front capital investment and a very long tail of monetization of said investment (because the same amount of revenue down the road is worth so much less than the initial outlay in real terms). With decreased investment comes decreased supply, further exacerbating the rise of prices. The adjusting of prices in the economy inevitably fails to keep pace, friction costs of transactions become prohibitive and economic activity, once frantic and spasmatic, seizes up just as surly as under sustained deflation. Not too pleasant either.

It is true that non-monetary assets may exhibit a certain level of resistance to the ill-effects of monetary volatility relative to monetary ones. This, however, is often overemphasized and misleading. Clearly money must exhibit 100% of the aggregate in-/deflationary trend, since it is the medium through which the phenomenon manifests and is measured in the first place. For an asset to ‘shelter’ you from monetary volatility better than currency it really does not need to be particularly extraordinary, it just needs to be less sensitive than 100%. Equity is the most likely to behave in this manner in aggregate. The more pricing power possessed by, less costly the friction of price readjustments, closer to continuous repricing and the more control over & the less need for capital-heavy (re)investment of a venture, the less adversely will it be affected by such monetary tectonics. But obviously, no business has perfectly frictionless and continuous pricing and therefore no asset will exhibit a non-positive sensitivity to monetary developments and thus every asset class suffers mechanistically from general monetary instability – no matter what anyone may claim to the contrary.

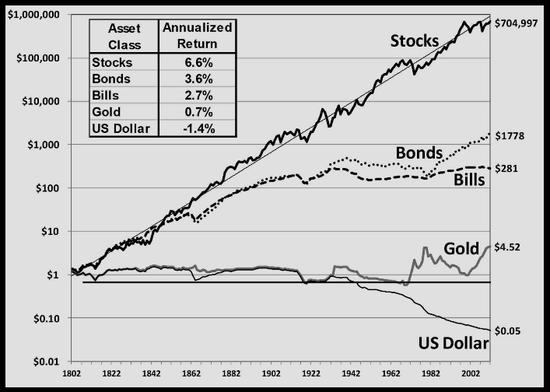

Now it is one thing to know what could conceivably happen to currency over time and an entirely different matter to observe it in vivo. Indeed, there seems to be a bias towards inflation in modern monetary history. The US-dollar for instance, has retained just 5 cents of purchasing power in real terms from 1802 to 2002. This example in particular is extraordinarily interesting since 200 years is a decently long period of time and includes intervals of both less and more active monetary intervention by central bodies (including the gold standard). Whichever way one turns the data, it is difficult not to note just how poor an investment currency makes in the long run. Despite this seemingly significant downside, the popularity and use of the US-dollar is undiminished. How come? Should a good currency not retain (or even grow) its value over time to make for a good medium of exchange?

Our three-choice-framework now enables us to make a significant observation: monetary assets’ price dynamics drive aggregate decision-making and balance between consumption, direct investment and saving. If a monetary asset has a deflationary long-term trajectory, it will displace direct investment, strangle consumption and the economy and eventually self-destruct without intervention. If the monetary asset loses purchasing power too quickly, it will naturally fall out of favor just the same, as discussed above. In theory, a currency that remains relatively constant in value ought to work reasonably well, except if you believe that its natural tendency is significantly inflationary, in which case its stability requires significant intervention by central bodies which would adversely affect capital allocation in other ways, such as the arbitrary restriction on credit growth relative to economic development of the gold standard. This, too, appears counterproductive and unsustainable in the long term. A steadily declining but not plummeting currency on the other hand, has several advantages. It remains stable enough to remain in use and still be a decent proxy for short- and medium-term real price changes. It also steadily hollows non-inflation-indexed obligations over time, reducing the burden of debtors in real terms at the expense of lenders. This constitutes wealth redistribution from passive capital allocators to entrepreneurial elements and may be a very important long-term factor facilitating economic development. It may even reduce the cost and risk of entrepreneurship through the aforementioned erosion of obligations, though the implications are highly complex and far-reaching and there likely are few savers or pensioners with completely unambivalent feelings on this particular issue.

Nevertheless, even if the effect on economic growth rates is very small, if it is persistent it will compound its way into enormous significance, given time.

Though of course there is much, much more left to be said about money, I hope that this small attempt at analysis has provided you with some positive real value

Tom