Inflation! What a word, what a concept! Even in circles free from the burden of practical or theoretical knowledge of finance and economics, it is possible to receive a lecture on hyperinflation, printing money, and, if one is particularly… lucky…, how blockchain technology experiences none of it. Unfortunately, it seems to me that many professional economists and commentators themselves struggle to attain a firm grasp of the phenomenon significantly superior to the above mentioned. And, to my dismay, this includes my not quite so humble self! Hence it is high time for a first step on the path to remedy and redemption. While in this post I will not make the popular error of attempting to forecast short-term inflation or deflation, I will disaggregate some of the aspects of the concept and perhaps even demystify some of them.

The very first thing to note, is that of course the rate of inflation is not caused by just one convenient factor but many messy interrelations and, much like body temperature, can be symptomatic of many different conditions but is sufficient to definitively diagnose at best only those situations where it has turned so extreme as to become a problem unto itself (i.e. hyperinflation, sustained deflation) and at worst none at all. And why should it? It is an incredibly broad measure, defined as the fall in purchasing power of currency or, equivalently, the rise of general price levels over time. As such, there are many different measures of inflation available over which to argue. What goods and services should be included in the basket of comparison, how should they be substituted as goods and services evolve over time, how ought they be weighted, how and where should real economic data be collected and accounted for, over what period should inflation be studied and so on and on. It is what one might diplomatically call an active area of discussion.

While these particulars are important and interesting, I am at present much more concerned with the question of the nature and origin of inflation, rather than its precise magnitude – much as one might ask why an organism’s body temperature is rising or falling over time rather than what its precise quantity is at any given instance. But enough tattle, onto the subject at hand.

Inflation, as it is measured and defined in units of currency, is naturally a monetary phenomenon. But – and I believe this is one of the reasons for the broad fascination it elicits – it equally relates to real productive output. In other words, it is the interface between the otherwise quite disparate worlds of money, and stuff, respectively. It is inflation that exposes the excessive issuance of currency to enable greater consumption as alchemy. Obviously, if there are three sandwiches in the global economy each costing a doubloon, producing more doubloons by itself will not allow you to eat four until someone makes another one of those baked prisons for charcuterie. Inflation therefore, is simply an aggregated measure of how much less one gets of a selection of goods and services, as a result of the relative rates of growth of the quantity available of that selection of goods versus the quantity of currency in circulation (that is, available to induce that transaction). If that mix of goods grew at the same rate as the relevant money supply, inflationary pressure would be zero. If money supply growth exceeded output growth you would get inflationary pressure equivalent to the gap and deflationary pressure in the converse scenario. Human-made stuff is finite, and the laws of physics cannot be swayed to allow otherwise, not even in exchange for some crisp bank notes still warm from the press (yes, I know, most money supply is digital, but that simply is not as evocative an image).

From this simple set of rules emerge more complicated expressions when looking at systems in motion and more representative of our world. Since the industrial revolution, all nations have experienced dramatic and continual increases to their productive capacity. The most successful of them have further seen another important transition away from manufacturing and turned into economies predominantly reliant on service and information-based activities. Since these changes materially concern the key inputs determining inflationary pressure (money supply and output) and the balance between them, it should not come as a surprise that they have also an important role in explaining inflation and the various proxies we choose to heed or ignore.

In an industrializing economy, one of the chief constraints of the growth of productive output is financial capital. In other words, the financing of the laying of railroad track, the construction of massive factories and machines and the turning to stone and steel of some seriously sexy bridges pulled from the late-night wet dreams of starchitects sucks up capital, making it scarce and expensive. Yet on balance these investments pay off immensely and the (autocatalytic) formation of more capital in the guise of machines, steel, concrete, labor and access to credit manifests in astonishing growth numbers and societal shifts. Each such investment also impacts inflation in a cyclical fashion over its lifetime. At the beginning, during the planning and funding phase, the investment absorbs scarce physical resources (in effect occupying some of the present capacity for output) and, being typically financed with credit, expands money supply. Aside from crowding out other possible investments, this causes inflationary pressure also and it is quite evident why: It widens the gap between available output and the supply of money chasing said output.

This pressure remains the same or levels off throughout construction and the phases of turning the investment productive (say bringing a factory online and reaching its cruising working capacity) based on the timing of financing and resource consumption. Yet, once the investment is starting to bear fruit, the initial phase reverses! Suddenly the factory/bridge/bank ceases to be a net consumer of the capital needed for further investments and turns net producer. It also starts repaying the credit once extended for the purpose of its creation, causing a contraction of money supply actively in circulation until the repaid money is once more extended to a new investment. Clearly, this is the opposite of our initial phase, reversing the inflationary pressure of the start and causing a deflationary force instead. So, over its lifetime, is the investment inflationary or deflationary? It depends. If the investment exactly pays for itself, it causes neither net inflation nor deflation over its lifetime. N.b. it still causes inflationary pressure in the beginning and deflationary pressure in its senescence, yet these offset in aggregate over its lifetime!

If, however, the investment is terrible and does not end up paying for itself, it then becomes clear that it is a net inflationary force. What though if it is a great investment? Then it simply causes net deflation in the long run. Should we therefore expect that economies in the process of successfully industrializing also are wracked by terrible bouts of deflation? Well.

Not necessarily.

You see, this is where it is important to once again look at the creature in motion. There is a reason why so far, I have carefully emphasized de/inflationary pressure rather than de/inflation, period. Because the deflationary pressure may be offset by the inflationary pressure of subsequent new investments (or simple consumption) and their phases overlap! If the economy keeps continuously reinvesting aggressively the returns of its prior investments and/or consuming them, the deflation may never self-evidently manifest as such and there may well be a sustained and positive rate of inflation, depending on the balance between successful mature investments’ return and the costs of new investments over time. A little bit like adding vectors of opposing forces in the Newtonian sense; the motion is an aggregate and determined by the net of the forces. The individual magnitudes of the forces are not readily apparent and only the resultant acceleration visible.

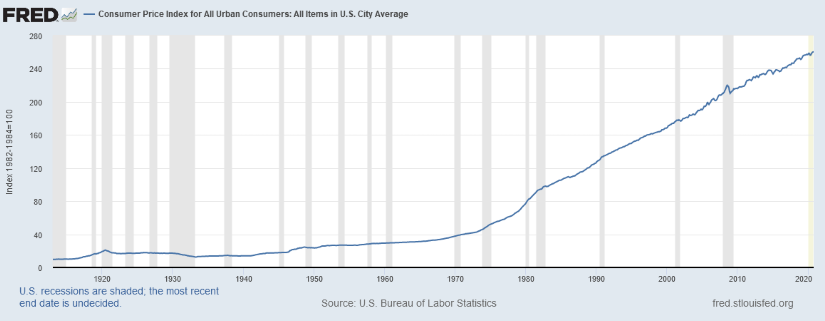

This explains, in my estimation, why inflation over the 20th century has been markedly positive. In any economy exhibiting positive real growth, aggregate investment has been productive by definition and caused significant deflationary pressures over time. Yet, victims of their own success, earlier investments’ high returns fund more and more subsequent investments and drive down the cost of capital by virtue of increasing its supply on steady or declining demand, while the returns of each subsequent generation of investment slowly diminish, as the obvious opportunities are made use of and the opportunity set becomes gradually less attractive. In this manner, deflationary pressure eases off at a faster pace than resource allocators choose to reduce growth in investment and consumption. With chronically low interest rates and a societal imperative for more growth without concern as to its longevity or substance, inflationary pressure ends up chronically dominating the deflation caused by productive stewardship of resources.

This framework also helps contextualize what common sense already dictates: the waves of growing household consumerism and appetite for radio, microwave, fridge, car, computer and so on are not coincidental but play an important part in absorbing the newly available productive capacity.

Further, it also now helps us make sense of the recent past and present. With investments becoming less productive in aggregate in post-industrialized economies, net lifetime deflationary pressure slows almost simultaneously as inflationary pressures from new big projects, now less attractive due to lower expectations of returns, decline. The balance looks remarkably stable, as the magnitudes of the inputs experience lower variance. I think this is a crucial realization.

Viewed in this way, it makes sense why the central banks who ‘tamed inflation’ cannot seem to hit their own two percent target rates, unfazed by even unprecedentedly aggressive and sustained interventions. They never were the predominant driver of inflation in the first place (unless they turned so extreme that they fell into hyperinflation like Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Turkey et al). The low interest rates drive little marginal capital formation and instead only serve to balloon financial assets and real estate – the former of which is not a part of PCE and the latter of CPI measures, respectively. Instead, cheap credit has warped security pricing of public and private markets, driven leveraging in risky and fragile areas and slowly hollowed out real incomes of middle classes and substituted them with growth-constraining dependence on consumer credit in the form of student loans, mortgages and other lifestyle related borrowing.

Clearly, I am not a fan of the path central banking has been taking us down since the latter half of the 20th century. But more on that in a future post.

I hope the above has been of interest to you

Tom