One of the many things I find gratifying about the world of finance is the eternal flow of case studies illustrating just how inseparably brilliance and utter folly coinhabit the human condition. As you may have heard, this month a family office – Archegos Capital Management – made quite the headlines.

Archegos (Greek; aptly, ‘one who leads the way’) under Tiger Cub Bill Hwang, had made a series of highly concentrated bets in a handful of stocks of rather debatable merit using total return swaps with half a dozen bulge bracket banks, levered those in total something like 5 – 8x and kept reinvesting any and all gains straight into the very same positions, to the point where it began driving the prices of those stocks up by virtue of its enormous size and leverage alone. We are talking about actual money here, with Archegos holding a 100 billion USD portfolio at its peak and Hwang’s share adding up to roughly 20 of those billions. It appears that this was the overwhelming majority of his net worth because yes, naturally, makes sense, of course, why would it not be.

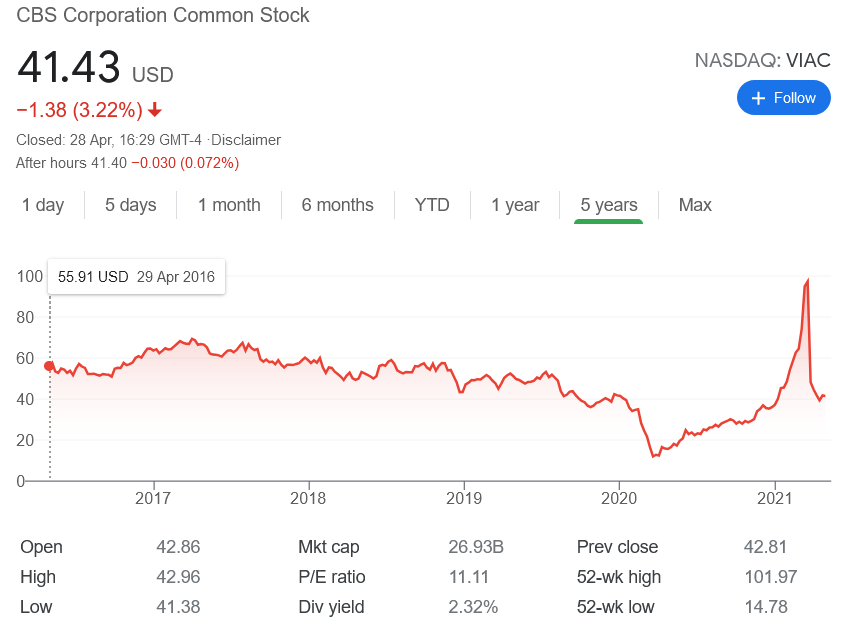

Now, this little dance with no strategic flaws whatsoever began in 2013 with a reported 200 million USD from a previous closed-down hedge fund and stepped to the jig quite merrily, making ludicrous returns right until it was margin called by some of its prime brokers when one core position in ViacomCBS faltered in price after an underperforming equity offering. Instead of taking the haircut but saving most of his many, many billions, Hwang doubled down and refused to exit his positions.

Finally, on March 26, Morgan Stanley and peers began liquidating the portfolio, triggering rumors on the Streets and extraordinary further declines in the price of the respective stocks. Led by Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Nomura et al ‘touched base’ over the weekend to try and coordinate the unwinding of these massive positions and cooling the incipient fire sale. Naturally, it did not work and the banks with lower exposures and sharper trading operations (namely Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, UBS and good ol’ Deutsche Bank) stampeded over the bodies of Credit Suisse and Nomura on the way to the exits. While it looks like the former names got away with sub 1 billion USD in nominal losses each, CS ate 5.5+ billion and Nomura 2.9+ billion of what looks like a cool 10+ billion USD systemwide thus far. If we were so unkind to include the prospective losses from tarnished reputations, inevitable fines, restructurings, golden parachutes for the exiting bankfolk and sign-ons for their replacement and half a decade of upcoming litigation, there is no question the bill will add many -ions more.

There is a lot to this story worth discussing and generally speaking, I would say there are two angles people are likely to focus on and one they are not:

Angle 1: Bill Hwang

Everyone loves a good villain as much as or even more than a good hero, particularly with younger Millennials and Gen Z being conditioned into greater externalization of the locus of control (see Thunberg shouting at politicians, generational wealth and income inequality, the hyper passive nature of the internet meme format). It should, hence, not be surprising when people wish to learn more about the ‘protagonist’ of this debacle. Who is this Bill Hwang character? Where did he come from, why have I only heard of him now? What is up with that whole Christianity thing?

And in all fairness, Hwang is interesting. Did you know for instance that he paid a 44 million USD insider trading settlement in 2012 and was banned from trading in Hong Kong for four years in 2014? That he founded a ‘charitable’ organization with 500 million USD in assets that may or may not be an obvious shell company designed for bribery and/or as a plan B for exactly the scenario that is currently unfolding, guaranteeing a multi-millionaire lifestyle retirement somewhere lush and sunny no matter what. While we are on that subject, he is also major donor to ‘Focus on the Family’, so much so that they gave him his own little bio. Just in case it was not sufficiently clear from his portfolio what kind of man Hwang is, here is a brief excerpt from the Wikipedia page on that particular organization:

“Focus on the Family promotes creationism, abstinence-only sex education, adoption only by heterosexuals, school prayer, and traditional gender roles. It opposes pre-marital sex, pornography, drugs, gambling, divorce, and abortion. It lobbies against LGBT rights, including LGBT adoption, LGBT parenting, and same-sex marriage. Focus on the Family has been criticized by psychiatrists, psychologists, and social scientists for misrepresenting their research in order to bolster its religious ideology and political agenda.”

Yup.

Angle 2: The Banks

Banks. We love to hate them. And it is easy to see why: In most people’s conception, banks are at best amoral and greedy and complicit in the 2007/8 crisis and at worst outright evil and single-handedly responsible for the real estate crash. So even though it is in some sense astonishing that all these sophisticated financial institutions decided to lend dozens of billions to a single client who at the time was a known inside trader all the while not knowing (not really wishing to know?) the true stupidity in quality and scope, of Archegos’ strategy, it also is not. And it is easy to take that perspective, run with it and pick out all the many poor decisions that were made at every one of those venerable institutions; e.g. how under Tidjane Thiam and his successor Thomas Gottstein, CS merged compliance and risk management departments, promoted Lara Warner (who had little background in risk management or compliance) to head of this chimera and pushed for the ‘commercialization’ of the risk management function.

And there are more than a few grains of truth to this narrative, too.

The problem with both of these popular takes on this type of story is that they leave all blame for these failures at the feet of the entities that are most obviously and directly involved in these breakdowns which A, does not help us figure out how to prevent these kinds of situations from happening in the future and B, neglects the culpability and indeed tacit complicity of supervising/delegating entities such as regulators, private interests, social norms, and, ultimately, us as individuals!

It is awfully convenient to a whole lot of us to go with narratives that abdicate our own responsibility whenever a crisis becomes too acute to ignore but this kind of behavior is in itself a key driver of what ails and holds us back as a collective.

Back at university I once had an argument with a classmate about this and it was stunning to me how seemingly everyone else in earshot took his position without questioning. These are genuinely bright people, too!

If you look at the 07/08 crisis for instance, who is to blame? My colleagues were ardent it was the almost exclusive failure of the greedy banks since they underwrote mortgages and loans to people of low & no creditworthiness. Banks evil, duh.

But if you reserve judgement for just a femtosecond, ask: What were the reasons the banks were giving out these mortgages in the first place when it was so obvious people could not afford them? Should banks not be trying to minimize losses on their loan book to maximize profit?

The superficial answer is that because banks could now securitize mortgages (CDO, MBS) and sell them off soon after origination, they did not bear the longer-term credit risk and hence did not have much incentive to be careful. And this is true. But why did this modus become so prevalent only in the 2000s in the first place, when MBS had existed since 1970?

- Retail banking had become less profitable because interest rates were artificially low as the Fed under Greenspan had sought to accelerate financial market recovery after the dot-com bubble burst (arguably the bubble had been inflated by the Fed’s overly easy monetary policy to begin with) and so banks were expanding into non-core lines of business

- Regulators determined (still do) capital reserve requirements of banks and financial intermediaries by assigning different risk weightings to different types of assets, including MBS, which meant that banks had incentives to favor certain assets, such as MBS, to attain lower reserve requirements and squeeze more profit out of their balance sheets

- The Big Three credit rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, Fitch) had been allowed by regulators to gain oligopolistic market share and not been regulated in a fashion that recognized the adverse selection dynamics at play in the space even with competition and therefore helped facilitate a systemic misclassification of the true risk underlying securitized credit

- The Bush & subsequent governments pushed (particularly via Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – which themselves had been created by the US gov in 1938 and 1970, respectively) for and subsidized aggressively the giving out of mortgages particularly to low income households for the purpose of ‘affordable housing’ and to be able to make politically expedient claims about how well the status quo worked for the poor and hollowing middle class

Further, artificially low interest rates (again, determined by the government entity that is the Federal Reserve) itself directly spurred on lending, financialization and speculation in numerous ways, such as by making loans of all kinds cheaper which meant more people were able and incentivized to take on higher leverage via mortgages, loans, and margin on their portfolios. Many of the people who had taken big losses on their speculative-at-best bets when the Internet bubble burst and felt that the stock markets were ‘rigged’ against them, enthusiastically reindulged in their minimally disguised gambling addiction and sought to outdo each other and get rich quick by repeatedly remortgaging or otherwise borrowing and speculating on real estate (e.g. ‘flipping’ houses). Yet others, who must have known that they could not afford the houses they were buying (because you do not go for a NINJA loan unless you have been rejected for more conventional arrangements and/or you already KNOW you will not be given one) did not hold back either.

As you can see, the Tango does not dance itself. It takes participants at all levels of society to make these massive dislocations happen. Of course, some actors are more significant than others; some weak points in the system more easy or difficult to address; some rules violated harder in one sector than another – but one cannot produce such concentrated systemic failure without willing and even knowing partakers.

In 9 AD, Publius Quinctilius Varus may have failed as a general solely in his own capacity… but why were there 3 legions trekking through Germania at all?

Rome – and its people – sent them.

This is – I believe – not a problem set that can be definitively solved. Humans will always feel the urge to cheat, to gamble, to transgress. Systems, rules and laws, too, will never be perfect and without gaps or captured-by-special-interests enforcement. Many a time the attempt at solving a past problem leads to the emergence of entirely new ones. Consider for instance the taxpayer-backed bailouts that are now commonplace. Are they entirely new? Of course not, financial institutions have been getting into trouble for as long as they have existed. The very notion of what a bank is has changed profoundly over the centuries: from goldsmiths, safekeepers, insurers, bureaux de change, lenders to aristocrats, merchant and trade financiers, loan sharks, real estate developers, investment firms to securities dealers, auctioneers, and deposit takers. The Fed itself (and federal deposit insurance schemes) was created to help stabilize the extremely fragmented banking system of the U.S., create confidence among savers and investors and prevent bank runs. Without the FDIC, the world of banking would look vastly different today.

What ought to be done? Should the state categorically cease to bail out financial intermediaries, indeed, abolish deposit insurance entirely so as to avoid creating moral hazard?

…

That to me appears a cure potentially worse than the disease, much like returning to the gold standard or bimetallism to offset some of the downsides of fiat. Society is a perpetually unfinished project, and we cannot but iteratively stumble forward, fall, rise again, collapse and get up once more only to keep flailing onward. But if we want to make our short lives, the few moves that fall into our generations’ hands count for not just us but our children and their progeny, we must not ignore that the ultimate and final backstop of institutions in a democracy is us. The voting majority. The original sovereign whose consent legitimizes the state and organs governing our society. If we as individuals choose to totally abdicate responsibility for corrupt and ineffective politics or imperfectly designed and imbalanced branches of government, then there is nothing else to right them. We fail by not even showing up.

It was disheartening for me to see that so many of my peers seemingly failed to acknowledge that reality. With such an outlook on life, it should not surprise us that there are many more Bill Hwangs yet to emerge.

It maddens and frustrates me nonetheless.

Tom

Ps: If you wish to read more in-depth about Bill Hwang, here is a good Bloomberg article – it even has pictures.