In late 2020, I wrote about my views on inflation and why I thought inflation as measured by PCE and CPI had been so consistently low for so many years, while noting that asset price inflation had been simultaneously much higher due to monetary policy. Looking back, I am quite happy with what I published then in most regards, with the exception that I only briefly touched on how asset price inflation affected the rapidly disappearing middle classes of developed economies:

“Viewed in this way, it makes sense why the central banks who ‘tamed inflation’ cannot seem to hit their own two percent target rates, unfazed by even unprecedentedly aggressive and sustained interventions. They never were the predominant driver of inflation in the first place (unless they turned so extreme that they fell into hyperinflation like Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Turkey et al). The low interest rates drive little marginal capital formation and instead only serve to balloon financial assets and real estate – the former of which is not a part of PCE and the latter of CPI measures, respectively. Instead, cheap credit has warped security pricing of public and private markets, driven leveraging in risky and fragile areas and slowly hollowed out real incomes of middle classes and substituted them with growth-constraining dependence on consumer credit in the form of student loans, mortgages and other lifestyle related borrowing.”

What I failed to make fully explicit is just how destructive this hollowing out of the middle classes has been and will be, and quite how the ‘preferred’ inflation measures’ exclusion of asset prices allowed for several decades of artificially cheap credit post 1987 (with savage acceleration after 2008 and during the pandemic).

Put simply, CPI and PCE by design exclude capital goods as they are meant to capture changes in the cost of consumer goods and services.

[Yes, both CPI and PCE encompass components meant to proxy the cost of shelter. However, Owner’s Equivalent Rent does not reflect changes in real estate prices accurately for many reasons. For one, the peak correlation coefficient of 0.75 between US house price growth and OER is reached at a time lag of a full 16 months, according to this Dallas Fed analysis. Similarly, rents and measures thereof do not always move with increases in house prices, especially when falling rates cause increased homeownership demand. Neither CPI nor PCE contain even remote proxies for financial asset prices or deposit yields.]

However, societal expectations for members of the middle class have long entailed meaningful ownership of capital — in the form of ownership of a house (tellingly, U.S. homeownership rates definitionally include mortgaged homes, with only 37% of households being mortgage-free), retirement savings invested in stocks and bonds, and plain old cash which, in theory, should be yielding a steady risk-free return in an FDIC-insured bank account.

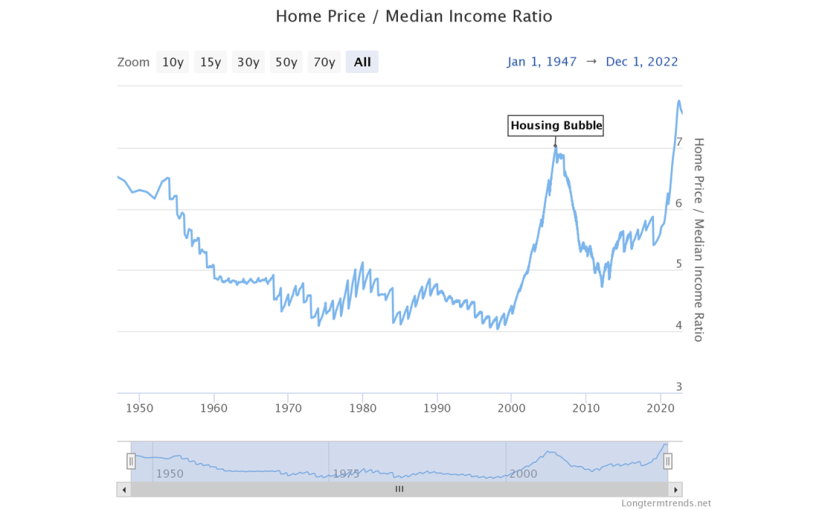

As the off-shoring of manufacturing and supply chains has kept consumer goods inflation low and even periodically negative, overall CPI looked deceptively low for many years. Meanwhile, interest rates plummeted, private and public equity skyrocketed, real estate soared higher than the boldest of bald eagles (importantly also as compared to median income), and savings accounts became cash incinerators in real terms. All of them remained unaccounted for by the conventionally accepted definitions of inflation which remained unchallenged by the economic orthodoxy. After all, why bother when ‘inflation’ was so low and the ivy league technocrat elite derived supreme legitimacy and unrestrained power from their ‘victory’ over the 08 crisis and inflation! To those young and less fortunate pursuing the dream of a ‘middle class’ life, the graduality and obscuring complexity of these enormous wealth transfers, excessively cheap consumer credit, and the propaganda suggesting that their lack of progress was due simply to lack of grit and hustle eventually became like water to the starving. The essential backbone of democratic stability and compromise, now afflicted with a Kwashiorkor promoted but simultaneously denied by a progressively narrower and intellectually homogenous political elite, became cheap to buy with premises of change of any kind, no matter from which end of the political spectrum. Alas, populism, once again, has revealed itself to be not the promise of genuine partnership, but the tenuous bond between client and supposed patron. The implicit social contract that has been supporting societal trust in what one might term liberal democracies is now viewed by large groups of people as fundamentally broken, with predictable consequences. I doubt that the decline in birth rates is solely attributable to the secularization of ‘richer’ countries, rather than growing pessimism about coming generations’ future prospects, for one.

Nevertheless, supposedly low inflation statistics and the manifold temptations of Keynesian stimulus masked the slow transition of emancipated citizens to neo-feudal serfs well enough to continue with unsustainable monetary (and, through deficit monetization, fiscal) policy. Indeed, perversely, the disenfranchisement of the economically most vulnerable has made them all the more prone to suggestions that negative real rates and QE were part of the solution to their problems, rather than their very cause. Amazing really, that with such high energy prices and economic fragility the likes of the ECB’s Lagarde, the BoE’s Bailey, and the BoJ’s Kuroda get such massive budgets for gaslighting.

But I digress.

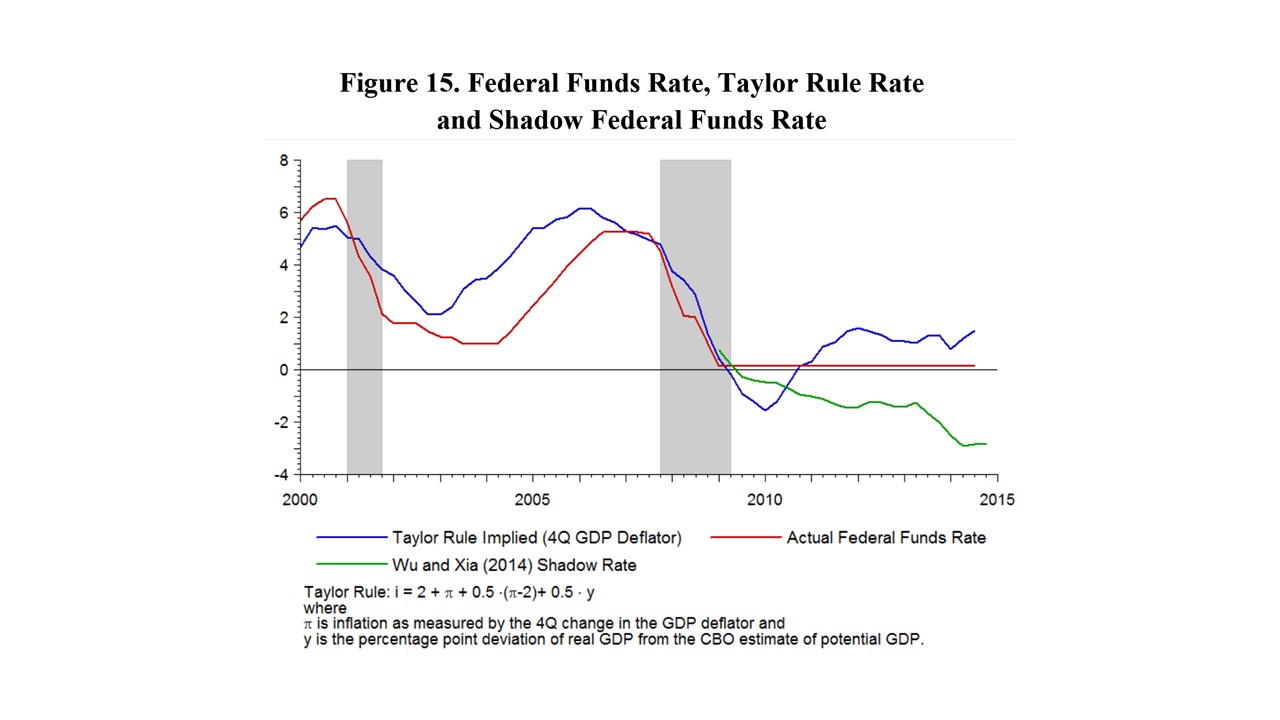

Even with such low inflation indicators unrepresentative of what they were supposedly measuring — namely, the decline in spending power as experienced by regular people due to aggregate price rises — such crude measures as the Taylor rule (itself relying on these deceptively understated definitions of inflation!) have shown massive divergence between policy and theoretically appropriate rates of interest for many years at both regional and global levels. Of course, once the absurdity of 0% and even negative rates became too difficult to ignore, some regimes, such as that of the United States, chose to use QE, a tool pioneered in modern times (2001) by the BoJ (after they themselves had introduced negative rates in 1999) to push more credit into the system than ordinary mechanisms would allow.

Source: https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/14110_-bordo–exiting_from_low_interest_rates_to_normality-_an_historical_perspective.pdf

Fast forward to 2023, and we can see what massive costs it would/will entail to normalize rates and central bank balance sheets. The (in relative terms small, but highly unusual) contraction in aggregate money supply in 2022 as a result of a very minor reduction in the Fed balance sheet, has led to deposit outflows across basically all banks, the consequent failure of Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank, and the ensuing loss of faith that ultimately felled the G-SIB that was Credit Suisse. For reasons that should be obvious, I will not comment on the regulatory actions taken in the context of these bank failures. In an abstract hypothetical scenario that by complete coincidence happened to resemble current goings-on but de facto bore no relations imagined or otherwise whatsoever, someone resembling my person but most definitively not me, might be tempted to suggest that these were bailouts of less-than-optimal structure that will exacerbate the longstanding buildup of moral hazard and dumbing down of financial market participants drastically. That person who is distinctly separate from mine, as I really cannot emphasize enough, would not be alone in that assessment.

Where to go from here?

In my estimation there are three different paths the developed economies could take in this context.

The first is to tighten monetary policy harshly (including some QT) and hence cause a recession with the corresponding increase in unemployment which would be politically unpopular but normalize asset valuations. I believe this is not likely take place for political and academic orthodoxy reasons (as evidenced by ECB and Fed officials implying neutral rates that are far too low, real interest rates continuing to be negative in US and Europe/UK, de Guindos calling for tools to limit core-peripheral EU government debt yield dispersion – I was in the audience that day and he seemed rather serious about the idea).

The second is to pursue long-term financial repression and keep real interest rates negative. To make this work, the European economies, the UK, and the US would need to introduce strict capital controls, as global capital flows would inevitably destabilize and make moot the attempted financial repression. I do not believe this to be particularly likely, but it certainly looks much more likely than it has in 30 or so years.

The third is to attempt financial repression/the tightening of monetary policy to levels insufficient to quell inflation without the introduction of effective capital controls. This would lead us into a stagflationary environment similar to the one pre-Volcker. This is my current base case. Naturally, there will likely be important differences to the late 60s and 70s of the previous century on the way there. I am not entirely certain what they will be. In fact, I am certain of perhaps only two things.

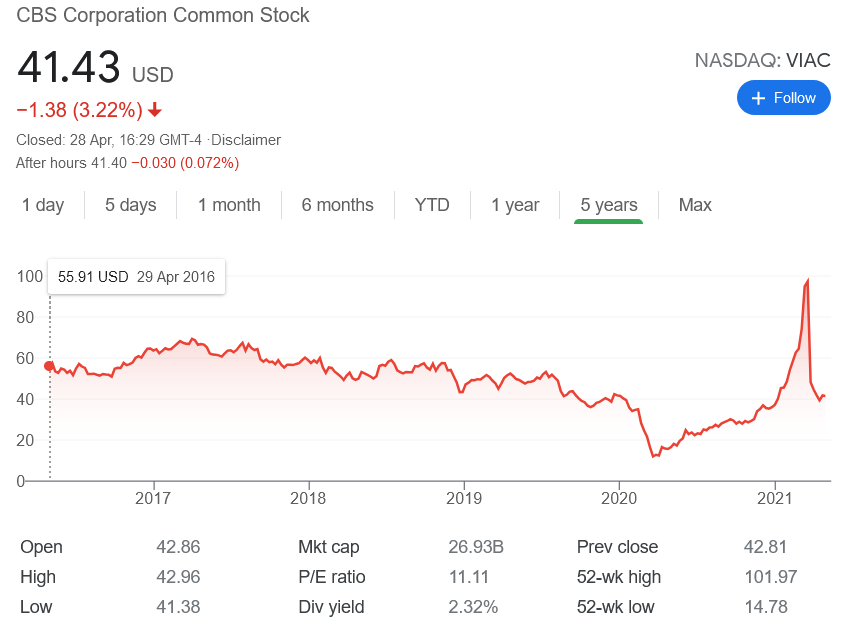

1. The real area of concern in the financial sector are not banks (and that is not to say banks will be completely unaffected), but shadow banks (that is, non-bank lenders). We will see the failure of many fintechs, Buy-Now-Pay-Laters, private equity funds, public funds, real estate firms, financial exchanges, hedge funds, venture capital outfits, family offices, factoring businesses, and whatever other vehicles have a business model that one way or the other relies on leverage.

2. We are now genuinely past the point of no return, and even the wisest policy must now focus on damage mitigation rather than avoidance. That is a pretty scary thought, even for me.

Let us hope we come out the other side renewed and primed for a better future, rather than ever more divided.

Tom

Ps: It sure looks to me as though regulators are aggressively backstopping banks because they know there will be many more illiquid but potentially solvent entities knocking about in the near future (as they are less willing to cut rates than market participants seem to think). Setting a precedent of successful orderly resolution of bank runs and financial institution failures without depositors being adversely affected would be a shrewd move… if state capacity were sufficient in the West to credibly handle these subsequent restructurings. Unfortunately I do not believe that to be the case and we will instead see more of a worst of both worlds outcome when inevitably the powers of the Fed are used too inefficiently and unwisely to keep the monetary pressure cooker going.